Items Similar to Perfect Service (La Bonne Table illustration)

Want more images or videos?

Request additional images or videos from the seller

1 of 16

Ludwig Bemelmans, 1898-1962Perfect Service (La Bonne Table illustration)ca. 1950

ca. 1950

About the Item

Ludwig Bemelmans (1898-1962). Perfect Service, ca. 1950. Brushed ink on paper, 19 x 24 inches. Annotated and authenticated by wife, Madeleine Bemelmans, in pencil en verso, 1979. Identified as illustration appearing on page 414 in La Bonne Table, (Simon and Schuster), 1964. Unframed.

Conservation work includes removal of tapes from verso corners, surface dry clean, removal of mat line and light exposure stains, deacidification and flattening.

"Writing is always a dreadful, tiresome business and the worst of all tortures for me, because I am convinced that I am not a writer but a graphic workman, a painter who hangs pictures in a row, who collects imagery, and my problem is always to find one for a beginning and one for an end and then, something to hang in the middle so that it resembles a book," said Ludwig Bemelmans (1898 - 1962).

Graphic workman, painter—whatever he called himself, Bemelmans belongs in the Pantheon of illustrators. A relentless connoisseur of life, he drew with a child's eye and wrote with the shrewd wit of an adult. He knew everyone worth knowing, went everywhere worth visiting, all the while recording what he saw on the backs of menus, envelopes, or on the inside covers of matchbooks. His resume was a checkerboard: hotelier, restaurateur, cartoonist, ad man, theatrical designer, novelist, screenwriter, interior decorator, journalist, and children's book author. What made Bemelmans such a creative powerhouse He confessed, "My greatest inspiration is a low bank balance."

His best-remembered work, of course, is the series of picture books starring that beguiling schoolgirl, Madeline. "I like to write for children because I suffer from a sort of arrested development. I am about six years old really," Bemelmans said, "and I am constantly surprised by everything." He knew that the Madeline books were his lasting legacy, yet it surely would have surprised him to find that they have sold upwards of ten million copies, and that the thriving Madeline merchandise empire now encompasses DVDs, dolls, board games, backpacks, tea sets, and stickers.

Bemelmans' world ranged from yachts and limousines to garrets and subways, and was peopled with moppets, jewel thieves, Ecuadorian Generals, and feather boa-clad vamps. His drawing style, humorous and reductive, captures all this in a flash. "I sketch with facility and speed," he wrote. "The drawing has to sit on the paper as if you smacked a spoon of whipped cream on a plate."

Born in Meran, Austria, and bred in Tyrolean hotels, Bemelmans came to the States at 16 and landed at the Ritz-Carlton. There he learned "to press a duck, open a bottle, and push a chair under a lady." While working his way from busboy to banquet manager, he drew, often using William Randolph Hearst's empty suite as his studio. The Ritz staff and clientele provided him with a rich menu of subjects, and he returned again and again to hotel life for inspiration.

He first set his heart on becoming a cartoonist. His earliest effort, The Thrilling Adventures of Count Bric A Brac (1926), ran for six months, but his big break happened when May Massee of Viking Press came to dinner. Admiring the scenes Bemelmans had painted on the blinds, Massee announced: "You must write children's books!" Hansi (1934), a reminiscence of his childhood, was quickly followed by three more: The Golden Basket (1936), The Castle Number 9 (1937), and Quito Express (1938).

Bemelmans met and married Madeleine (Mimi) Freund in 1934. The two honeymooned in Belgium, which provided the setting for The Golden Basket, his Newbery-Honor winner. Not many realize that Madeline makes her debut in this book. Madeleine, spelled like his wife's name here, is one of 12 little girls shepherded by a tall nun through the streets of Bruges.

In 1938, Bemelmans, Mimi, and their two-year-old Barbara traveled to France. On the recommendation of Georges, his underworld friend, Bemelmans visited the Ile d'Yeu off the coast of France. Here came more inspiration for Madeline when he was knocked off his bike by a truck. He had to walk to the hospital, where, in the next room, he wrote, "was a little girl who had had her appendix out, and on the ceiling over my bed was a crack that, in the varying light of morning, night and noon, and evening, looked like a rabbit."

He went on: "I remembered the stories my mother had told me of life in the convent school at Altotting, and the little girl, the hospital, the room, the crank on the bed, the nurse, the doctor, all fell into place. I made the first sketches on a sidewalk table outside the Restaurant Voltaire . . The first words of the text were written on the back of a menu in Pete's Tavern on the corner of Eighteenth Street and Irving Place in New York."

In a rare moment of poor judgment, Massee rejected Madeline. Although she thought the manuscript was cartoon-like, Bemelmans' readers were charmed. Bemelmans had found his true audience, which he described as, "clear-eyed, critical and hungry . . . all of whom are impressionists themselves, who love my pictures, and sometimes even eat them. They are children." Madeline won Caldecott Honors, and the sequel, Madeline's Rescue, won the Caldecott Medal in 1954.

How useful for Bemelmans that he was both artist and writer. The typewriter may have been his enemy, but as his bibliographer Murray Pomerance wrote, "his manuscripts reproduced like snails." He turned out hundreds of illustrated magazine articles, anthologies, novels, children's books, and countless ads for everything from Jello to Tabasco. Bemelmans was also an acute marketer: he advertised his books by pre-publishing a chapter in a magazine, and then after the book launched, sold the artwork at the Kennedy or Ferargil Galleries.

Bemelmans averaged about two books a year, but he also produced an astounding amount of interior design. Like an unruly child with a box of crayons, he embellished walls wherever he went. He painted murals for Hapsburg House, a Viennese restaurant on 55th Street in New York. He decorated Jascha Heifitz's bar, and designed sets and costumes for a Broadway play.

In Hollywood, Bemelmans' office sported a picture of a lion having its way with Louis B.

Mayer (painted out the minute the artist left). Aristotle Onassis asked Bemelmans to create murals for the playroom of his yacht. In Paris, Bemelmans painted scenes on the walls of his auberge, La Colombe, and the Inn's sign, a dove, on a piece of zinc from the bar.

In his own home, Bemelmans was equally busy. At one of his Gramercy Park apartments, he glued a map of Paris to the ceiling of the bedroom. An insomniac, he lay in bed with a flashlight, taking nocturnal strolls along the banks of the Seine. The dining room sported a parade of painted donkeys with real straw hats.

Then there is one of the great charm spots of Manhattan, the Bar at the Hotel Carlyle. Gentle mayhem rules in this alternate universe, where animal families dressed in their Sunday best stroll through Central Park. Madeline and the Bad Hat perform circus tricks on the lampshades, and in a snowy corner, an equestrian statue stands. On the base is carved "BEMELMANS '47."

He painted this marvel in exchange for 18 month's free rent at the hotel. It is a monument to his lasting and multi-generational appeal.

A Toulouse-Lautrec lady from one of his novels summed up Bemelmans' style. Sweeping past a debutante, she remarked in a Dorothy-Parker-like aside, "Sugarwater, let Champagne show you how it's done." Bemelmans at his best—but then he was truly a superlative vintage.

- Creator:Ludwig Bemelmans, 1898-1962 (1898 - 1962, American)

- Creation Year:ca. 1950

- Dimensions:Height: 19 in (48.26 cm)Width: 24 in (60.96 cm)

- Medium:

- Period:

- Framing:Framing Options Available

- Condition:

- Gallery Location:Wilton Manors, FL

- Reference Number:1stDibs: LU24527188282

About the Seller

4.9

Gold Seller

These expertly vetted sellers are highly rated and consistently exceed customer expectations.

Established in 2007

1stDibs seller since 2015

329 sales on 1stDibs

Typical response time: 2 hours

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Ships From: Wilton Manors, FL

- Return PolicyA return for this item may be initiated within 7 days of delivery.

More From This SellerView All

- Same Old Story (Brooklyn Dodgers & St. Louis Cardinals Illustration)Located in Wilton Manors, FLBill Crawford (1913-1982). Original illustration artwork depicting teams as they advance to the World Series. Depicted are representations of the St. Louis Cardinals and The Brooklyn...Category

1940s Realist Figurative Paintings

MaterialsPaper, Charcoal, Ink, Gouache, Pencil

- Coronel Retirado y Su Amante Esposa (Cuban Artist)By Felipe OrlandoLocated in Wilton Manors, FLFelipe Orlando (Cuban-Mexican, 1911-2001). Coronel Retirado y su Amante Esposa, ca. 1970. Ink and gouache on paper with heavily built up layers of textured ground. Measures 13 1/4 x 18 3/8 inches. Signed lower left. Original label affixed on verso. Excellent condition. Unframed. An anthropologist as well as a painter and engraver, Orlando, whose full name was Felipe Orlando Garcia Murciano, studied at the University of Havana and at the painting workshop of Jorge Arche and Víctor Manuel. He was a founding member of the Asociación de Pintores y Escultores de Cuba (APEC) and a professor at the Universidad de las Américas and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, both in Mexico City. His style is influenced by the Afro-Cuban movement and pre-columbian art...Category

1970s Abstract Abstract Paintings

MaterialsInk, Gouache

- The Soda Fountain (New Yorker Magazine cover proposal)Located in Wilton Manors, FLBarbara Shermund (1899-1978). The Soda Fountain, ca. 1950s. Watercolor and ink on paper, 9 x 12 inches; 13 x 16 inches framed. Signed lower right. Exc...Category

Mid-20th Century Realist Figurative Paintings

MaterialsInk, Watercolor

- Life Magazine Art Deco Showgirls CartoonLocated in Wilton Manors, FLBarbara Shermund (1899-1978). Showgirls Cartoon for Life Magazine, 1934. Ink, watercolor and gouache on heavy illustration paper, matting window measures 16.5 x 13 inches; sheet measures 19 x 15 inches; Matting panel measures 20 x 23 inches. Signed lower right. Very good condition with discoloration and toning in margins. Unframed. Provenance: Ethel Maud Mott Herman, artist (1883-1984), West Orange NJ. For two decades, she drew almost 600 cartoons for The New Yorker with female characters that commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony. In the mid-1920s, Harold Ross, the founder of a new magazine called The New Yorker, was looking for cartoonists who could create sardonic, highbrow illustrations accompanied by witty captions that would function as social critiques. He found that talent in Barbara Shermund. For about two decades, until the 1940s, Shermund helped Ross and his first art editor, Rea Irvin, realize their vision by contributing almost 600 cartoons and sassy captions with a fresh, feminist voice. Her cartoons commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony, using female characters who critiqued the patriarchy and celebrated speakeasies, cafes, spunky women and leisure. They spoke directly to flapper women of the era who defied convention with a new sense of political, social and economic independence. “Shermund’s women spoke their minds about sex, marriage and society; smoked cigarettes and drank; and poked fun at everything in an era when it was not common to see young women doing so,” Caitlin A. McGurk wrote in 2020 for the Art Students League. In one Shermund cartoon, published in The New Yorker in 1928, two forlorn women sit and chat on couches. “Yeah,” one says, “I guess the best thing to do is to just get married and forget about love.” “While for many, the idea of a New Yorker cartoon conjures a highbrow, dry non sequitur — often more alienating than familiar — Shermund’s cartoons are the antithesis,” wrote McGurk, who is an associate curator and assistant professor at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. “They are about human nature, relationships, youth and age.” (McGurk is writing a book about Shermund. And yet by the 1940s and ’50s, as America’s postwar focus shifted to domestic life, Shermund’s feminist voice and cool critique of society fell out of vogue. Her last cartoon appeared in The New Yorker in 1944, and much of her life and career after that remains unclear. No major newspaper wrote about her death in 1978 — The New York Times was on strike then, along with The Daily News and The New York Post — and her ashes sat in a New Jersey funeral home...Category

1930s Art Deco Figurative Paintings

MaterialsInk, Gouache

- Fancy Department Store Satirical CartoonLocated in Wilton Manors, FLBarbara Shermund (1899-1978). Fancy Department Store Satirical Cartoon, ca. 1930's. Ink, watercolor and gouache on heavy illustration paper, panel measures 19 x 15 inches. Signed lower right. Very good condition. Unframed. Provenance: Ethel Maud Mott Herman, artist (1883-1984), West Orange NJ. For two decades, she drew almost 600 cartoons for The New Yorker with female characters that commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony. In the mid-1920s, Harold Ross, the founder of a new magazine called The New Yorker, was looking for cartoonists who could create sardonic, highbrow illustrations accompanied by witty captions that would function as social critiques. He found that talent in Barbara Shermund. For about two decades, until the 1940s, Shermund helped Ross and his first art editor, Rea Irvin, realize their vision by contributing almost 600 cartoons and sassy captions with a fresh, feminist voice. Her cartoons commented on life with wit, intelligence and irony, using female characters who critiqued the patriarchy and celebrated speakeasies, cafes, spunky women and leisure. They spoke directly to flapper women of the era who defied convention with a new sense of political, social and economic independence. “Shermund’s women spoke their minds about sex, marriage and society; smoked cigarettes and drank; and poked fun at everything in an era when it was not common to see young women doing so,” Caitlin A. McGurk wrote in 2020 for the Art Students League. In one Shermund cartoon, published in The New Yorker in 1928, two forlorn women sit and chat on couches. “Yeah,” one says, “I guess the best thing to do is to just get married and forget about love.” “While for many, the idea of a New Yorker cartoon conjures a highbrow, dry non sequitur — often more alienating than familiar — Shermund’s cartoons are the antithesis,” wrote McGurk, who is an associate curator and assistant professor at Ohio State University’s Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum. “They are about human nature, relationships, youth and age.” (McGurk is writing a book about Shermund. And yet by the 1940s and ’50s, as America’s postwar focus shifted to domestic life, Shermund’s feminist voice and cool critique of society fell out of vogue. Her last cartoon appeared in The New Yorker in 1944, and much of her life and career after that remains unclear. No major newspaper wrote about her death in 1978 — The New York Times was on strike then, along with The Daily News and The New York Post — and her ashes sat in a New Jersey funeral home...Category

1930s Realist Figurative Paintings

MaterialsInk, Gouache

- Woman with Red HairLocated in Wilton Manors, FLBaron Robert Heinrich Freiherr von Doblhoff (1880 Vienna - 1960 ibid.) Woman with Red Hair Ink and watercolor on paper, image measures 6.25 x 7.25 inches; 12.75 x 13.5 inches fra...Category

Early 20th Century Vienna Secession Portrait Paintings

MaterialsInk, Watercolor

You May Also Like

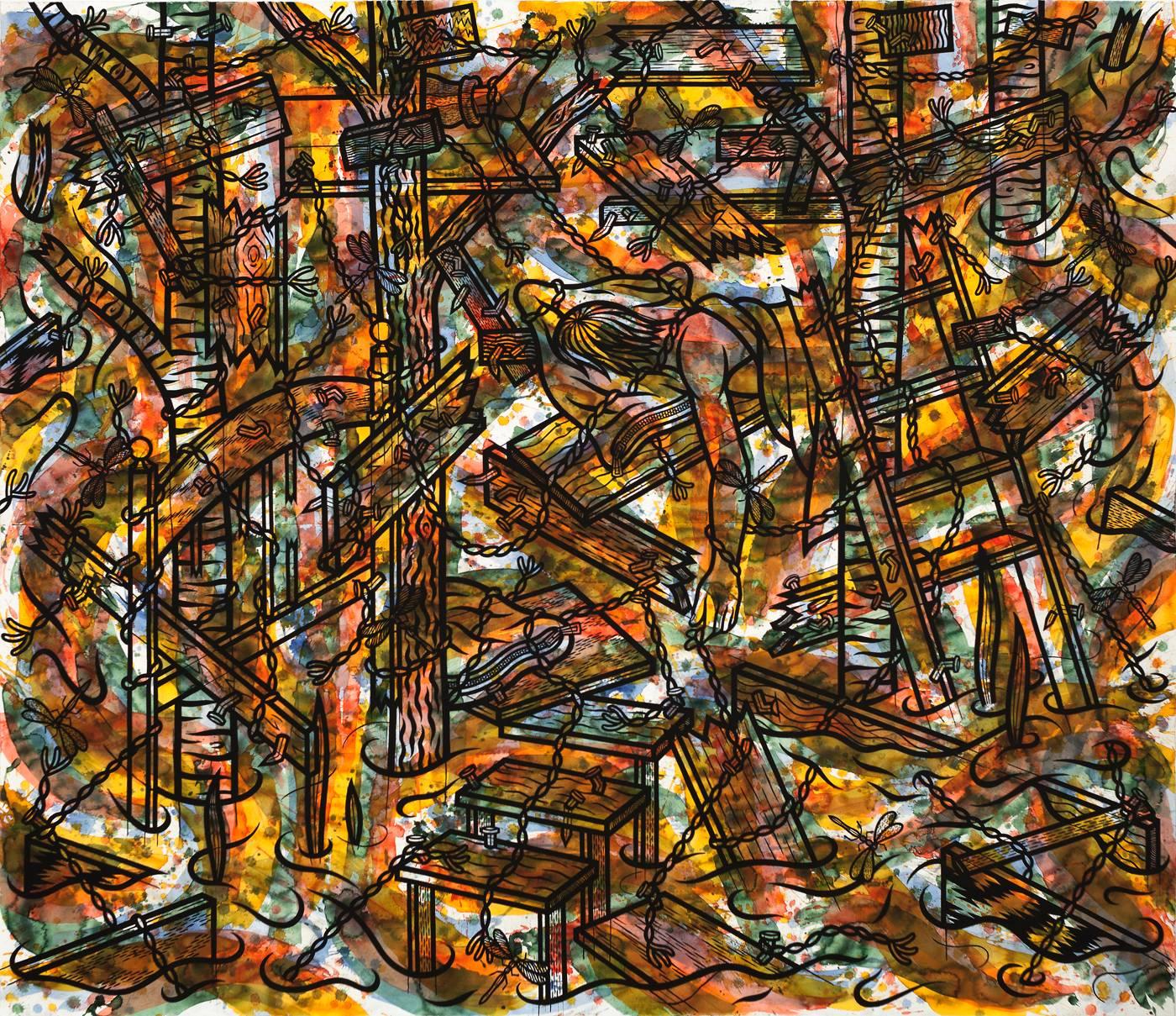

- RestBy Jesse LambertLocated in New York, NYink and watercolor on paper, 82" x96" This painting is from a new series of works by Jesse Lambert which ink and depict ad-hoc structures that are constructed out of scraps of woo...Category

2010s Contemporary Abstract Paintings

MaterialsArchival Paper, Watercolor, Archival Ink

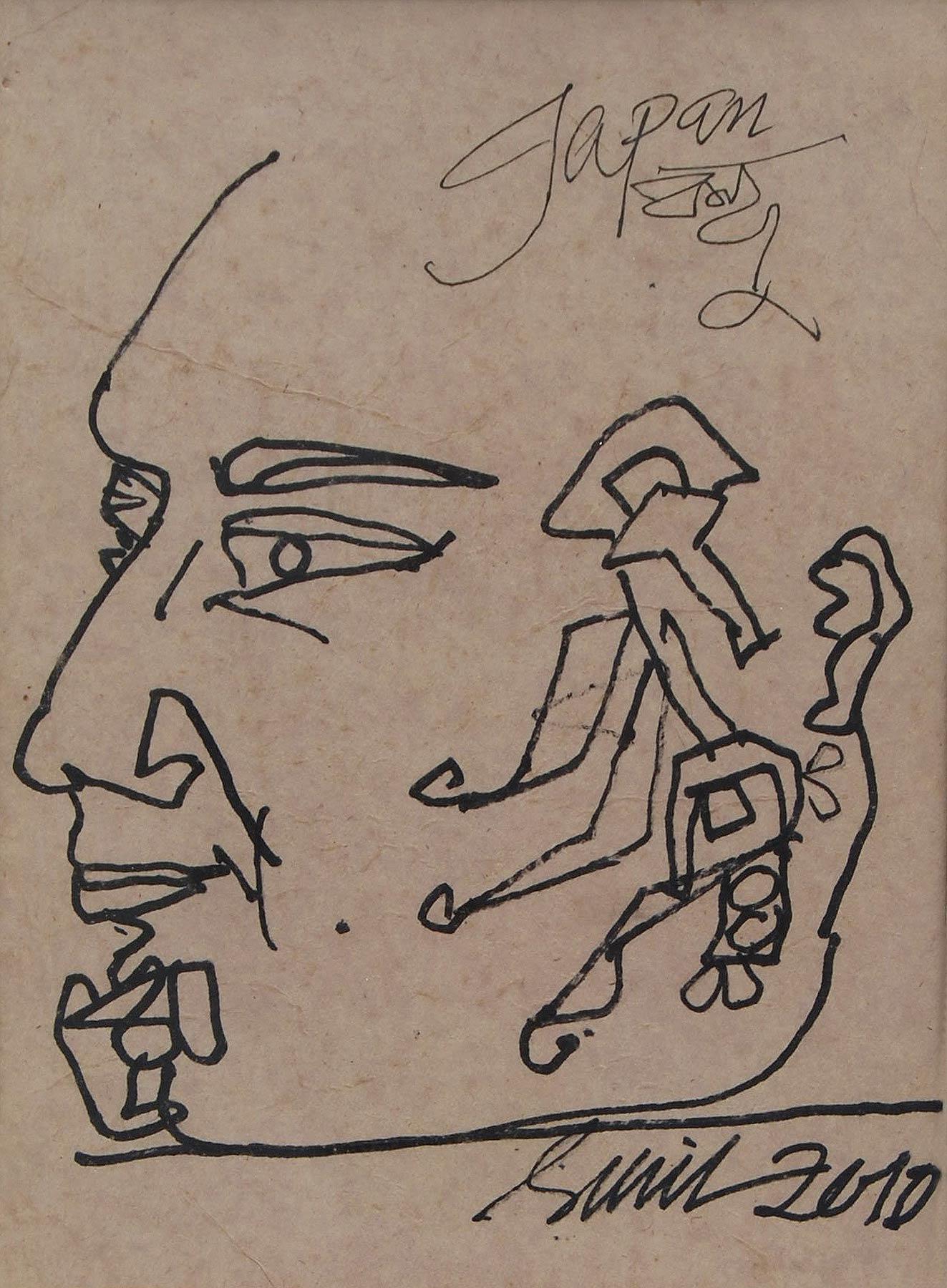

- Head, Japan Bandhu, Ink on Paper, Black, Brown by Indian Artist "In Stock"By Sunil DasLocated in Kolkata, West BengalSunil Das - Head - 9.25 x 7 inches (unframed size) Ink on Paper Inclusive of shipment in ready to hang form. Sunil Das (1939-2015) was a Master Modern Indian Artist from Bengal. Ext...Category

2010s Modern Figurative Paintings

MaterialsInk, Paper

- Suzanna and the EldersBy Ben ShahnLocated in Miami, FLA modern interpretation of the biblical story Suzanna and the Elders. Signed lower right Ink and wash on paper The Downtown Gallery Felix Landau Gallery Ernest Brown & Phillips, Ltd...Category

1940s American Modern Portrait Paintings

MaterialsWatercolor, Ink, Gouache, Archival Paper

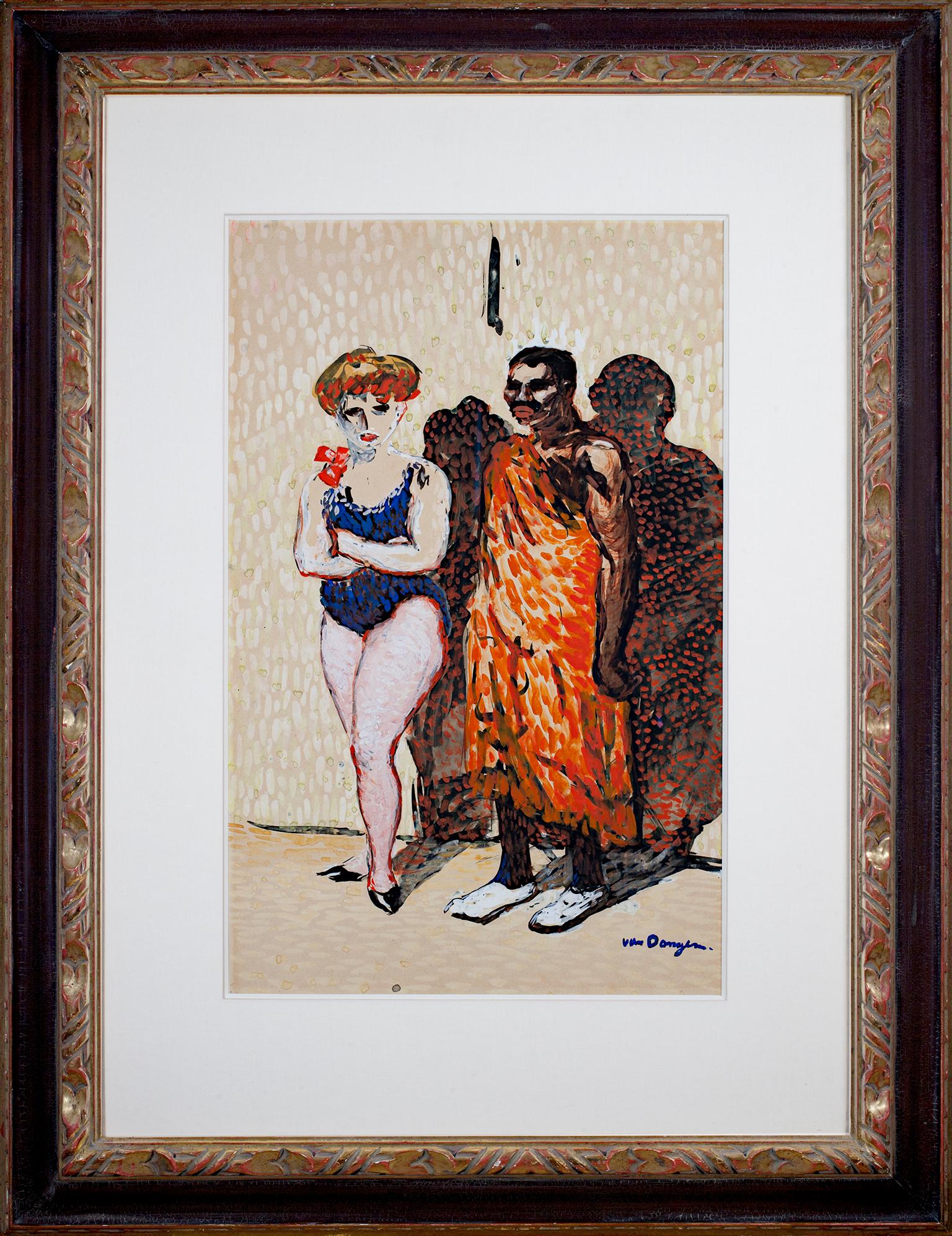

- Kees Van Dongen Circus Performers 1900s Vintage Vibrant Figure Fauvist SignedBy Kees van DongenLocated in Milwaukee, WI"Les Artistes du Cirque" is an original painting in ink, watercolor, and gouache on paper by leading Fauvist artist Kees Van Dongen, signed in the lower right. In the piece, two circus performers stand against against a wall. On the left, a pale woman in a blue leotard with red flowers on the shoulder stands with her arms crossed, looking out at the viewer. The painter fills in her tights with delicate white brushstrokes, lending them an almost iridescent appearance. Her strawberry blond hair is piled on top of her hair according to the fashion of the period. On the right, an African man stands in a vivid orange toga, looking somewhere off to the left. His feet are clad in bright white shoes...Category

Early 1900s Fauvist Figurative Paintings

MaterialsPaper, Ink, Watercolor, Gouache

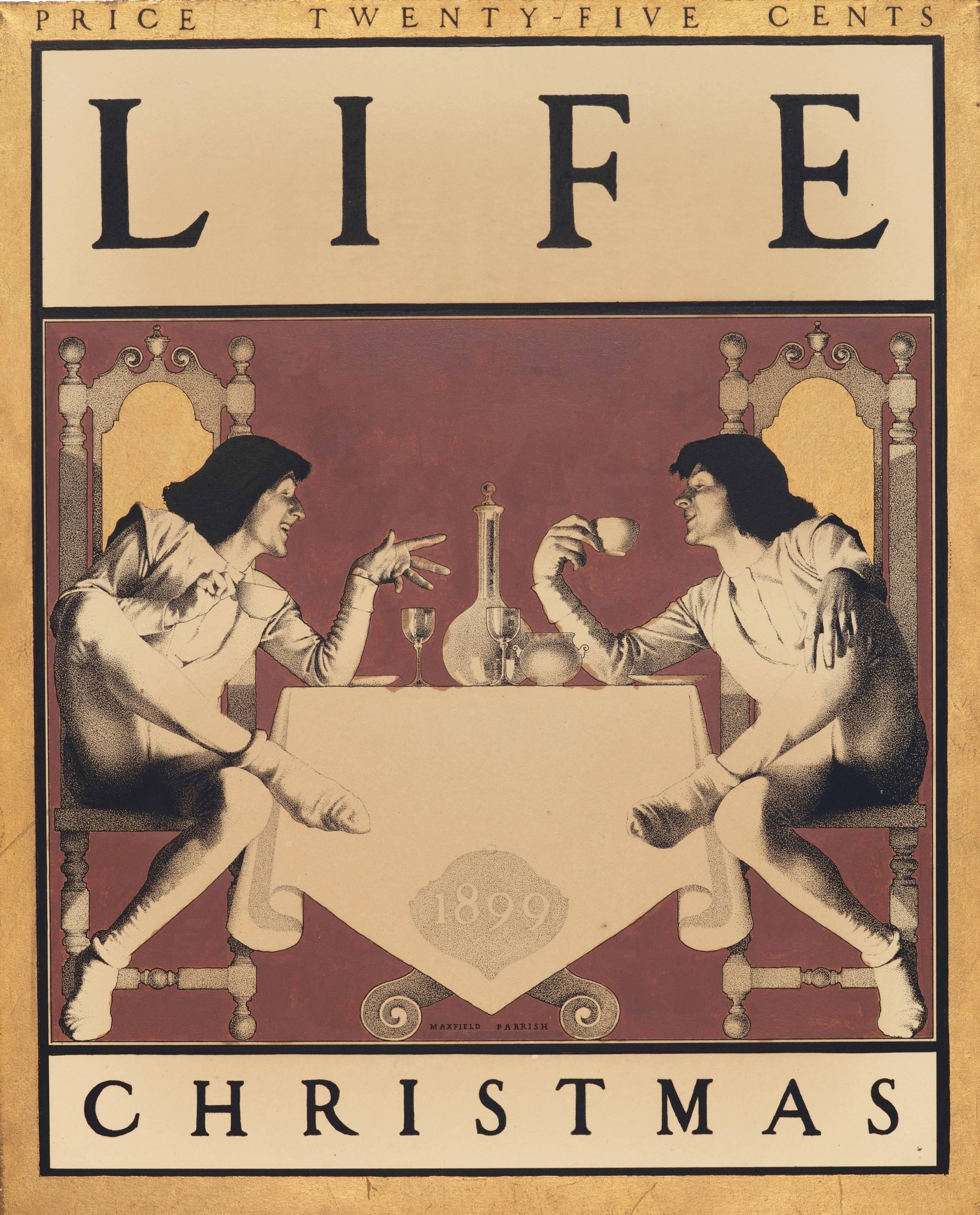

- Christmas Cover Design for Life MagazineBy Maxfield ParrishLocated in Fort Washington, PAMedium: Oil, Ink and Gold Leaf on Paper Dimensions: 15.00" x 12.00" Signature: Signed Lower Center The present work was published as the cover of the December 2nd, 1899 issue of Lif...Category

Early 20th Century Figurative Paintings

MaterialsGold Leaf

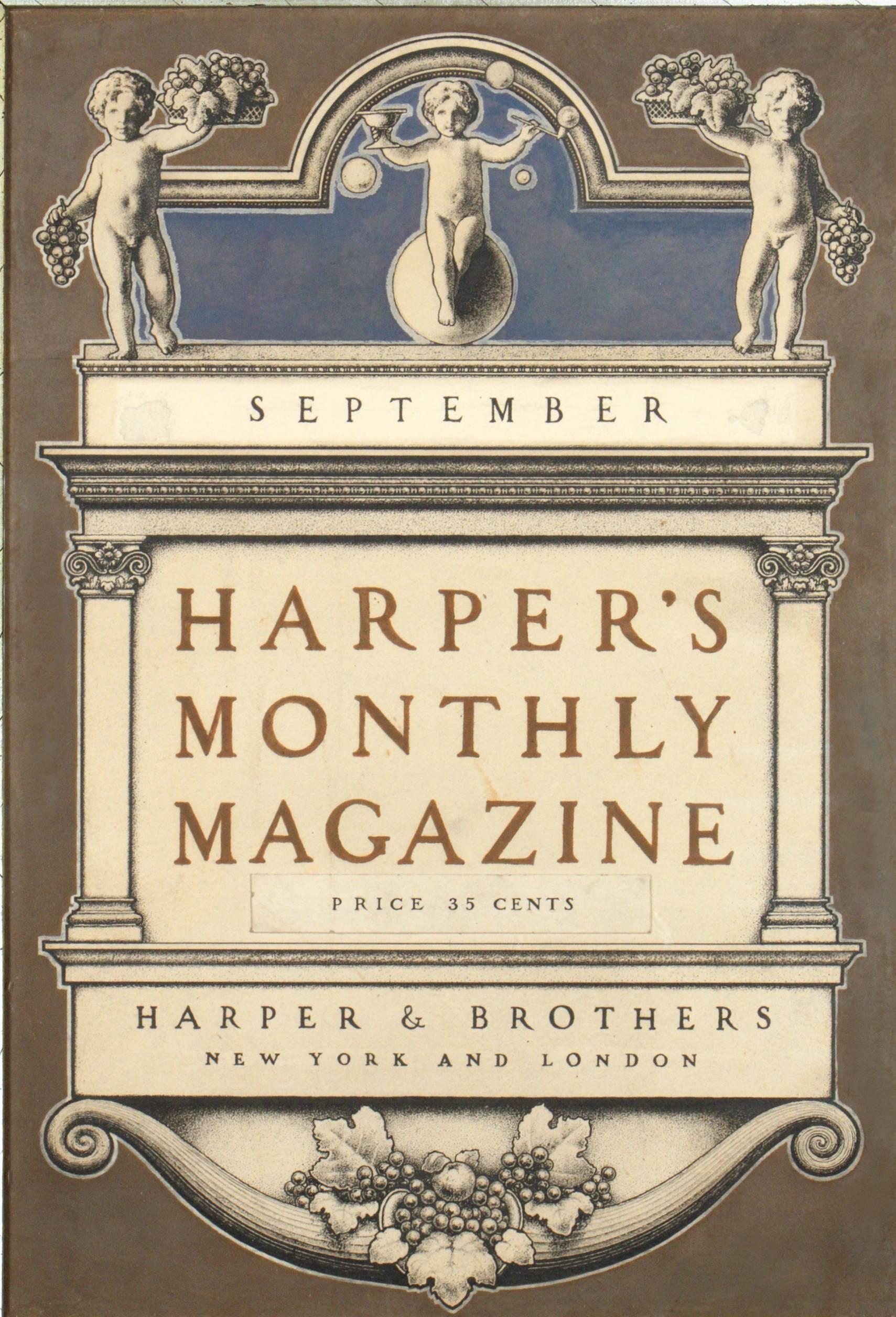

- Harper's Monthly Magazine CoverBy Maxfield ParrishLocated in Fort Washington, PAMedium: Oil and Ink on Paper Signature: Unsigned Sight Size 13.75" x 9.50"; Framed: 17.25" x 13.25" Harper's Monthly Magazine Cover, September 1900 Notes on Verso: "Nelson: Art Dept. Harper's Magazine: Pay Maxfield Parrish $50 for design. Also use Christmas Magazine...Category

Early 1900s Figurative Paintings

MaterialsOil, Paper, Ink

Recently Viewed

View AllMore Ways To Browse

French Illustration

Paris Illustration

Illustrations Set

Past Perfect

French Illustrations Vintage

Illustration Room

Mid Century Illustrations

La Parade

Vintage Illustration Style

Set Design Illustration

1950 Illustration

Children Illustration

Childrens Illustrations

Illustration Art 1950

Retro Mid Century Illustration

Vintage Illustration Man

Ludwig Vintage

Uses Of A Service Plate